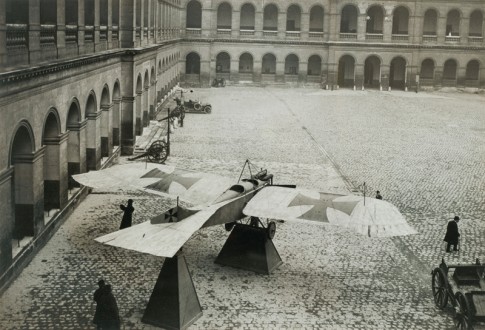

A captured German Taube monoplane, 1915. This German plane was called “Taube”, meaning “pigeon” or “dove” in German. It was designed by Igo Etrich (1879-1967), an Austrian engineer. Its fuselage and tail were modelled after a pigeon. This plane was displayed in the courtyard of the Hôtel des Invalides from 1915 to 1917, along with pieces of artillery. In 1914, it made an emergency landing in the Meuse following an engine failure. Captured, it was considered a “war trophy”. Its display was aimed to show visitors an aircraft that was closest to those that had flown over Paris in early 1914. The wing and tail are decorated with a simplified version of the Iron Cross, the German national symbol. © Paris, musée de l’Armée, Dist. RMN-GP / Pascal Segrette

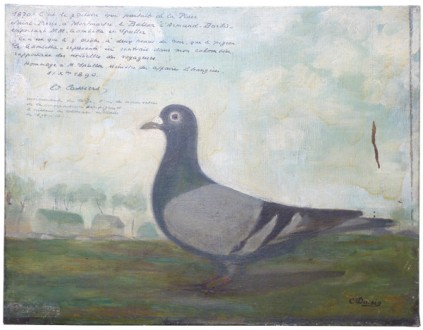

Homing Pigeon « Le Gambetta ». Oil on canvas by C. Ducoin, ca 1890. A handwritten inscription on the upper left corner of this painting reads as follow: “1870 – It is on October 7, that the balloon “L’Armand-Barbès” rose from Saint-Pierre square with MM. Gambetta and Spuller. It was not until October 9, at two o’clock in the evening that the homing pigeon “Le Gambetta”, pictured here, returned to my dovecote bringing back news from the travellers. A Tribute to Mr. Spuller, Minister of Foreign Affairs. December 31, 1890. Ed[ouard] Cassiers” Édouard Cassiers was a pigeon fancier. As president of the Parisian pigeon-fanciers’ club L’Espérance, he recruited several pigeons during the Siege of Paris. He was one of the organizers of the Pigeon Post during the siege. His dovecote was installed in his apartment located at 92 Boulevard du Montparnasse in Paris. © Paris, musée de l’Armée

“Paris besieged: My pass? Hold on?” Fine earthenware plate decorated by Jules Renard alias Draner (1833-1926), ca 1871. This plate was manufactured by the Creil-Montereau potery factory. Its illustration evokes the role of ballooning during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and its importance regarding communications. During the Siege of Paris, which begun on September 20, 1870, all communications with the rest of the country were cut. Belgian pigeon fancier, Louis Van Roosebeke introduced the idea of putting homing pigeons in the baskets of hot-air balloons. French photographer Nadar (1820-1910), founded the Compagnie des Aérostiers Militaires so that passengers and homing pigeons could be transported by air. Unfortunately, few homing pigeons managed to return to the city due to the severity of the weather and poor training. When Gambetta left Paris aboard the Armand Barbès balloon on 7 October 1870, one of the pigeons taken on board returned to its home coop two days later, with news from the travellers © Paris, musée de l’Armée, Dist. RMN-GP / Émilie Cambier RMN

The Homing Pigeons. Anonymous photograph. 1914-1918

Bus mounted mobile pigeon loft, 1918 by Camille-Albert Le Play (1875-1964). The first mobile lofts appeared in the middle of 1915. They were created by converting double-decker buses. In the French army, the most widespread was the araba-colombier, a horse-drawn mobile pigeon loft containing between forty and sixty homing pigeons. In November 1918, more than 350 mobile pigeon lofts were still in service in the French army. © Paris, musée de l’Armée

The pigeon

A Messenger since Antiquity

Since Antiquity, homing pigeons have been used to carry dispatches, such as the announcement of the winner of the Olympic Games. They are also used in commercial networks and Julius Caesar employed them to transmit information on enemy troop movements. This practice persisted during the Crusades, and later on during the sieges.

The twentieth century marks the birth of a new sport: pigeon racing. In 1870, over 800 racing homers were brought to the Museum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. During the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), they became the only means of communication between the besieged French capital and the rest of France. The birds were flown safely over the Prussian lines by floating balloons and flew back to Paris with their precious dispatches. However, this pigeon service could not prevent from disinformation since the Prussians were able to capture some only to release them with bogus dispatches.

At the end of 1914, as the war of stagnation developed and the entrenched armies turned to positional warfare, means of communication became of vital strategic importance. The pigeons’ homing abilities, even under the most dangerous conditions (gas, bombardments), secured the delivery of dispatches and messages when other means of transmission – telephone lines for example – were cut.

Home pigeons were also used during the Second World War during which 16,500 birds were fitted with mini parachutes and air-dropped into occupied France in order bring intelligence back to Britain. During the First Indochina War (1946-1954), they were used for liaisons between outposts in a remote location in the jungle and their command post.

Pigeongrams: miniaturizing the Official Dispatches

Before 1840, messages carried by homing pigeons were simply rolled and placed in a goose-quill tube that was tied with a thread to the tail feather of the pigeon. Various methods for transporting messages were tested. At the beginning of the First World, the use of aluminium or rubber canisters fixed to the bird’s leg with a ring was significantly widespread. Initially, the dispatches were hand-written on thin paper; later on they were micro-photographed. The process of microphotography allowed for a much reduced size of the folio pages that could contain thousands of dispatches. The microfilm was projected on screens by means of a Megascope, a type of magic lantern.

Military Dovecotes

After the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), the Telegraphic Section of the French Corps of Engineering created a homing pigeon service. Military dovecote was the result of long term collaboration between the military and civilians. In accordance with the Law of 3 July 1877, pigeons were subject to requisition, in the same way as horses and mules. In accordance with the Decree of 5 September 1885, the “civilian” pigeon census and the right of requisition were also regulated. In 1888, eight military dovecotes were established in Paris, Vincennes, Perpignan, Marseille, Belfort, Lille, Toul and Verdun. Operating a dovecote and using homing pigeons were both regulated by the Law of 22 July 1896. In 1919, the French Federation of Pigeon Fanciers was created. And it was not until the passing of Ministerial Order of 28 June 1926 that the rules of the organization of military dovecotes were finally clearly defined.

Around 1895, the French 24th Battalion of the 5th Engineers Regiment, composed of pigeon fanciers and telegraphists, was stationed in Fort Mont-Valérien. It was later transferred to the 8th Engineers Regiment in 1912. Nowadays, the dovecote of the 8th Signal Regiment of Suresnes stationed in Fort Mont-Valérien, is the last remaining military dovecote in France.

Honouring our War Heroes

The heroic services of the birds during the two World Wars were fully recognized. This is the reason why, “Cher Ami” of the US Army Signal Corps was awarded the French “Croix de Guerre” with palm for saving 194 men of the “Lost Battalion” of the US 77th Division of Infantry during the Battle of Argonne, in 1918. As for “Vaillant”, it was during the battle of Verdun that he illustrated himself in order to save Major Raynal and his besieged garrison, in a difficult position in the Fort Vaux. The bird was awarded a Certificate of Merit of the Carrier Pigeon Ring and a grant of the summons to the Order of the Nation of French Pigeon Fanciers. The stuffed bodies of “Dear Ami” and “Vaillant” are respectively kept in the National Museum of American History in Washington DC and the Musée des Transmissions in the Fort Mont-Valérien. In addition, a memorial “to the 20,000 pigeons that died for their country” and “to the pigeon fanciers who were executed by the enemy for having kept them” was erected in Lille, in 1936. After the Second World War, 46 pigeons were awarded the PDSA Dickin Medal.

Ajouter un commentaire