First French Republic, 1795. Infantry and Camel Regiment in Egypt. Lithograph by Jules by Jules Renard alias Draner (1833-1926). The above lithograph by Belgium cartoonist Draner, taken from the 1863 series depicting “Military Types”, gives us a fanciful picture the Campaign of Egypt. It could very well be that Draner was inspired by the name the Greeks used to give to ostriches: strouthokamelos, meaning “camel-sparrow”. © Paris, musée de l’Armée

A twentieth century lead figurine inspired by a lithograph by Draner, on exhibit in the Cabinets Insolites of the Musée de l’Armée. © Paris, musée de l’Armée.

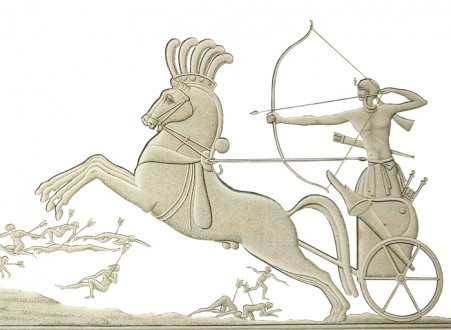

A description of Egypt. Three Egyptian kings can be seen bow hunting ostriches. The eggs of this bird that can reach 65 km per hour, is reputed for its medicinal values and is used as an antibiotic on open wounds and cranial fractures while its fat is used to relieve muscular and arthritic pain. But it is mostly its much coveted feathers that attract premium prices. The ostrich was sacred in Ancient Egypt and its feathers were associated with many deities, amongst which the Goddess Ma’at who personified perfect cosmic and earthly equilibria. On the scale which represented balance and justice, the “Feather of Ma’at” was used as the counterweight in the weighting the hearts of the dead which had to be at least as light as the feather so that Ka, the defunct vital essence, could gain eternal life. The ostrich feathers also ornamented the headdresses of Pharaohs and war horses pulling their chariots. © Paris, musée de l’Armée.

The Ostrich

The War Ostrich as a Mount?

Is the ostrich a formidable war mount? Alas, for the poor French infantryman taking part in the French Campaign in Egypt, reduced to drag himself barefoot in the sand, the wish to roam the desert like the proud meharist (in the ancient texts, the Arabian camel is referred to as mehari) riding on his dromedary, can only be a dream. In the annals of war, no traces were found on the domestication of ostriches, at any time.

Without prejudging the pertinence of this expression, we must point out that it is an incorrect observation. The ostrich is fully capable of using its physical potential to protect itself and can also outrun danger with great speed and manoeuvrability.

However, ostriches are abundantly referred to in the military annals through the false metaphor of the so-called “Ostrich Policy”. This compelling image derives from Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) who wrote that ostriches “imagine, when they have thrust their head and neck into a bush, that the whole of their body is concealed”. Thus, the myth of the ostrich sticking its head in the sand was born. Wrongly believing this animal to be stupid, Pliny the Elder turned the ostrich into a symbol representing people who are too stubborn to know any better than to “hide their head into the sand”, that is who prefer to ignore a problem instead of facing it, hoping that denying the existence of a danger will make it go away, even if this implies being completely caught off guard. This expression has been used for centuries to denounce politicians who refused to take into account signs or early warnings of a military conflict.

It is well known that the emu possesses an excellent instinct of preservation, but can also prove to be an excellent military strategist as demonstrated by its victory in the Great Emu War, the first inter-species war between humans and emus. In 1932, following the request of farmers in Western Australia – most of which had fought in the Great War – the Australian Army approved a special defence measure in order to stop the incursion of a large number of emus that were spoiling and ravaging their standing crops on their farms. As months passed, the military operation fought with Lewis guns against this emu army proved unsuccessful and in the end, it was the simple fence that solved the problem.

For further reading: “The Great Emu War: In which some large, flightless birds unwittingly foiled the Australian Army” in Scientific American, August 4, 2014.

Ajouter un commentaire