Camouflage is the art of concealment and deception. The French Army became the first to establish a Camouflage Section in February 1915 in order create visual deception and protect soldiers and equipment from observation by enemy forces. Soon, each nation became expert in the art of camouflage. In France, several painters, decorators and prop masters were assigned to the Camouflage Section whose symbol was the chameleon. Concealed observation posts, camouflage nets and dummies proliferated on the ground, as is shown on this photograph representing a papier-mâché dummy cow.

Origines de l’artillerie française, planches autographiées d’après les monuments du XIVe et du XVe siècle avec introduction, table et texte descriptif par Lorédan Larchey, Paris, 1863. © Paris musée de l’Armée

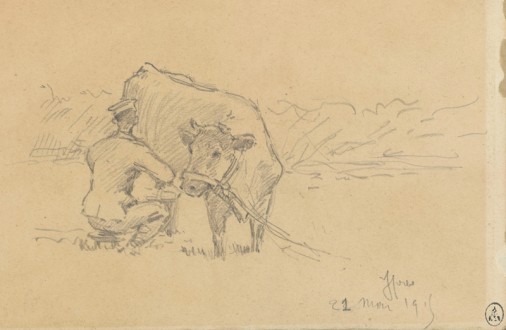

Ypres, 21 May 1915. Drawing by Georges Touff Alouis (1889-1918). © Paris, musée de l’Armée Dist. RMN-GP / image musée de l’Armée

The Cow and The Bull

Feeding the Army

“BEEF” (noun) – [from BULL]. A word derived from Latin and Greek “bos”, “bous”, and considered here a staple food for the Army (…) – The Regulations 13 May 1818, labelled beef as “the meat which must be considered to be the FOOD FOR THE TROOPS. – The need for food for an ARMY is estimated one ox per one thousand men. – Beef belongs to so-called FORTRESS GOODS, either as a standing animal or as CORNED BEEF”. (Dictionnaire de l’armée de Terre by Étienne Alexandre Bardin, vol 2, 1841-1851, p. 788).

Symbolically, the horns of the last bull killed to feed the Parisians, during the siege of Paris in 1871, are preserved, mounted on a wooden stand (Museum of Art and History of Saint-Denis).

During the First World War, butchers followed the armies with herds of cattle and pigs. In his book Journey to the End of the Night (1932), French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline tells in a scene of slaughter that took place at the beginning of the war: “On sacks and tent cloths spread out on the grass there were pounds and pounds of guts, chunks of white and yellow fat, disembowelled sheep with their organs every which way, oozing intricate little rivulets into the grass round about, a whole ox, split down the middle, hanging on a tree, and four regimental butchers all hacking away at it, cursing and swearing and pulling off choice morsels”. From the start, war of movement, retreats and exhausted animals made transportation more difficult. From November 1914, army meat supplies switched to frozen meat imported from Argentina or Australia.

To Equip and Transport

If the cow and bull meat are primarily used in the army to feed the troops, they also serve as raw material to manufacture equipment. In ancient times, the Scythians had their helmets made of ox hide; the Roman used the clipeus, a shield covered with leather. In France during the eighteenth century, soldiers’ equipment was often made of cowhide, as specified in the royal warrant of 19 January 1747 on clothing regulation of the Infantry by which it was specified that each infantry soldier was to carry a “red or black cow hide giberne and a pouch”.

During the French invasion of Russia, Napoleon supplemented the artillery train by establishing new battalions drawn by oxen in order to spare the horses. On 6 January 1812, he addressed a letter to the Comte de Cessac, then Minister of the Administration of War, requesting a report on the cost and the capabilities of these animals. On 22 January, he asked his stepson Eugene de Beauharnais, viceroy of Italy, to form another ox-drawn battalion since “the kingdom of Italy has many oxen; it is a way to use them”. On 24 January, Napoleon notified to the Comte de Cessac that he wished to have four more ox-drawn battalions consisting of 1,224 wagons and a horse-drawn battalion from the Kingdom of Italy, harnessing 306 wagons, all destined to the Artillery Train.

Ajouter un commentaire