British troops entered the German town of Eupen (now in Belgium) on 1 December 1918. A summarily-fashioned Arch of Triumph was erected at the entrance to the city. The houses were not decked in flags, the inhabitants attending were few in number and not particularly welcoming. To the right, on the light wall, a panel decorated with the German eagle announced the entrance to the city. Eupen was annexed to Prussia after the Vienna Congress in 1815, then to Germany during the German unification of the 1870s. © Paris, musée de l’Armée

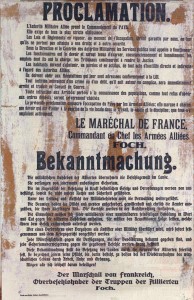

This poster was up all over Prussia-Rhineland from 30 November 1918. © Paris, musée de l’Armée.

This poster was up all over Prussia-Rhineland from 30 November 1918. © Paris, musée de l’Armée.

On 15 November 1918, Marshal Foch laid down the rules of the occupation regime drafted in accordance with the agreements resulting from the 1907 Hague Convention. It outlined four occupation areas in Rhineland. Three major cities: Koblenz, Mainz and Cologne. In each, bridgeheads boasting a 30 km radius were built on the right bank of the Rhine. Beyond these bridgeheads, a neutral, non-militarised zone stretched 10 km from the Dutch border to the North, to the Swiss border to the South. The regions of Mainz, Koblenz, Cologne, Mannheim and Wiesbaden under the responsibility of the Allies were in the Western European time zone, while the rest of Germany continued to go by the timetable defined by the MEZ. © Paris, musée de l’Armée

Occupation

From the end of November 1918, Allied and associated troops entered Germany, though the occupation would not start until December.

It began with a show of strength as troops paraded in front of the Allied and/or associated military authority, an event to which the local population was “convened” by poster. Symbolic gestures were made, such as that of General Degoutte, who, in December, delivered his speech in front of the tomb of Charlemagne in Aachen; General Plumer, head of the 2nd British army, attended the march of troops, on 12 December, in front of the statue of Prince Hohenzollern of Prussia.

The military authority met with the city’s civilian leaders. The occupying troops were set up in buildings that were already built or remained to be built, sometimes with the financial aid or labour of the city. The Occupant’s flag was omnipresent in the city.

The military authority could intervene in the daily life of the city by adding street or building plaques in the language of the occupants; by organising cultural events, like General Fayolle who, at the beginning of January, gave a series of public concerts and an exhibition on the traces left by the French Revolution and the First Empire in the region. It could also signal its presence by setting up trophies, such as cannons, taken from opponents, or machines testifying to its power, such as tanks, on symbolic or very frequent places.

The occupation was generally little appreciated by the people, especially as the country’s western border had not been crossed during the four years of war.

Ajouter un commentaire