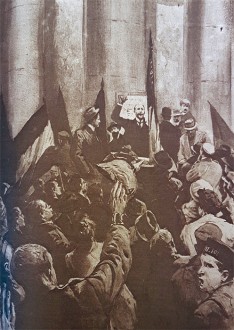

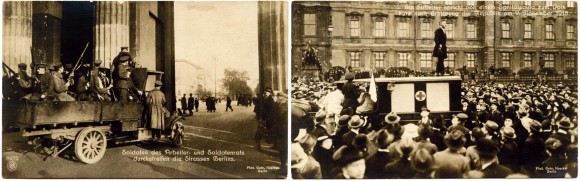

To the left, “Workers and Soldiers Council walking the streets of Berlin”. On the right, “A worker announces the introduction of a medical car for the people shortly after the Republic was declared on 9 November 1918”. On the same day, with the political and military authorities fearing that Germany will tumble into a Bolshevik-style revolution, echoing the events just a year earlier in Russia, a call was issued for a general strike. Many workers and soldiers headed for the centre of Berlin. They would occupy the factories and official buildings. The Republic was then proclaimed twice in the afternoon. The first time around 2 PM, from the Reichstag, by the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann, and a second time around 4 PM hours from a balcony of the château, the main residence of the Hohenzollern, by Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919), who proclaimed a Socialist Republic. © Private collection.

This image from Le Miroir shows the State Secretary without portfolio in Prince Max de Bade’s Cabinet, Philipp Scheidemann (1865-1939), in front of the Reichstag, Berlin, on 9 November 1918. It states: “The Emperor has abdicated. He and his friends are nowhere to be found, the People’s victory over them is complete. Prince Max von Baden has passed on the role of Chancellor of the Reich to Member of Parliament Ebert. Our friend will form a labour government, in which all the socialist parties will participate”. A sailor is placed clearly in the fore, at the bottom right of the image, to recall the October 1918 revolt. While the German Admiralty has instructed its fleet to attack the British Home Fleet , a number of sailors, not wanting to sacrifice themselves for a lost war, were arrested. At the beginning of November, in the port of Kiel, located on the Baltic Sea, red flags were flown on the warships to protest the arrests… © Paris, musée de l’Armée.

This image from Le Miroir shows the State Secretary without portfolio in Prince Max de Bade’s Cabinet, Philipp Scheidemann (1865-1939), in front of the Reichstag, Berlin, on 9 November 1918. It states: “The Emperor has abdicated. He and his friends are nowhere to be found, the People’s victory over them is complete. Prince Max von Baden has passed on the role of Chancellor of the Reich to Member of Parliament Ebert. Our friend will form a labour government, in which all the socialist parties will participate”. A sailor is placed clearly in the fore, at the bottom right of the image, to recall the October 1918 revolt. While the German Admiralty has instructed its fleet to attack the British Home Fleet , a number of sailors, not wanting to sacrifice themselves for a lost war, were arrested. At the beginning of November, in the port of Kiel, located on the Baltic Sea, red flags were flown on the warships to protest the arrests… © Paris, musée de l’Armée.

On 9 November, Friedrich Ebert proclaimed the victory of the revolution and called the workers and soldiers to peace. On 10 November, he instituted the Rat der Volksbeauftragten, the Council of the Representatives of the People. This new government succeeded thanks to the support of General Wilhelm Groener, who replaced General Ludendorff as of 29 October 1918. On 11 November 1918, under pressure from the German General Staff, the government accepted the end of fighting and Matthias Erzberger signed the armistice in Compiègne. In 2014, in an interview, the German historian Arndt Weinrich recalled that 11 November “is not anchored in the German memory”. 9 November, on the other hand, is an important date with “the abdication of Guillaume II, and the proclamation of the Republic, known later as Weimar. © Paris, musée de l’Armée

November 1918, Germany

Germany’s naval blockade, undertaken as early as 1914 by the Royal Navy, led Germany to seek armistice. It was in fact maintained after the signing on 11 November 1918 to force Germany to sign the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919. It led to undernourishment in the Germans and their allies, causing riots in Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Other factors need to be taken into account, such as the Russian Revolution of October 1917 and the negotiations in Brest-Litovsk, which culminated on 3 March 1918 in the signing of a peace treaty.

From Revolt to Revolution

Many warning signs, from January 1918, of demoralisation among civilians, disobedience and desertions in the military, went ignored or were masked by the Supreme Command of the Army, and in particular by Ludendorff. From July 1918, however, the German population was hit on its territory by Allied aviation attacks, while many letters from the front and the accounts of the perpetrators were alarming the Germans about the superiority of the enemy in aeroplanes, artillery and tanks, and the Americans were proving tenacious and aggressive fighters according to historian Pierre Jardin.

In September, more specifically 29 September, when the Bulgarian armistice was announced, Ludendorff demanded that a request for peace be made as no longer a military solution could be found any more.

October, Zusammenbruch

In October 1918, the new Chancellor, Max de Bade, sent a note to the US president “to ask him to take charge of restoring peace”. The event came so brutally and so suddenly that it seems incomprehensible. His contemporaries referred to it as a collapse (Zusammenbruch). The change of government allowed the German Military Staff to disengage from the request for armistice, giving rise to the myth of a stab in the back – Dolchstosslegende – who claimed that only the German revolution had caused defeat. In the country, tensions continued to mount all the way to the revolutions of early November.

Ajouter un commentaire